What about meta-arts?

This blogpost has been written by Ben Kretzler. Ben is a PhD student of our meta-research group and started his PhD in September 2024. During his PhD, he will be working on Jelte’s Vici project: Examining the Variation in Causal Effects in Psychology with his supervisors Jelte Wicherts, Marcel van Assen and Robbie van Aert.

According to Wikipedia, we use the term "metascience" for the application of scientific methodology to study science itself. But there's perhaps another reason to talk about meta-science: within the arts and sciences, it seems that primarily the latter have a substantial number of researchers dedicated to scrutinizing research practices and assessing the confidence we can have in our knowledge.

To explain this, we could put forward several reasons: First, theories from the sciences often yield statements whose content is easier to falsify compared to the statements we can derive from theories from the arts.¹ Therefore, overconfidence in or flaws of theories from the sciences might be more easily detectable than those of theories from the arts. Second, and relatedly, meta-research movements in fields like medicine and psychology often arise as reactions to "crises of confidence"—when results don't replicate or scientific misconduct is uncovered (Nelson et al., 2018; Rennie & Flanagin, 2018). Since evaluating the arts' function can be more challenging, such confidence crises may simply occur less often, perhaps reducing the pressure for self-evaluation.²

Still, even if these reasons help explain why meta-research in the arts has not reached the same intensity as its counterparts in the sciences in the past, they are insufficient to explain why such meta-research is not happening in the present. In this post, we will argue that meta-research in the arts is not only possible but necessary, exemplified by cases from quantitative history and cultural studies.¹

Quick Detour: What Is the Current State of Meta-Arts?

As pointed out above, the meta-researcher-to-researcher ratio in the arts seems to be far below that in psychology or medicine. Consequently, evidence regarding publication bias, selective reporting, or analysis heterogeneity is sparse. Still, there are some individual projects that (directly or indirectly) addressed the replicability and robustness of research in the arts:

The X-Phi Replicability Project, which tested the reproducibility of experimental philosophy (Cova et al., 2018) by conducting high-powered replication of two samples of popular and randomly drawn studies. It yielded at a replication rate of 78.4% for original studies presenting significant results (as a comparison: the replication rate for psychological research stemming from 2008 seems to be around 37%; Open Science Collaboration, 2015).

A part of the June 2024 Issue of Zygon was devoted to a direct and a conceptual replication of John Hedley Brooke's account of whether religion helped or hindered the rise of modern science, as explored in his book Science and Religion. While the replicators mentioned a few minor inconsistencies in how Brooke presented the theses of some other researchers and interpreted some original and newly added source material differently than Brooke, they acknowledged that his work was of high quality and did not challenge his general account. Thus, although this historical work and its underlying sources beard some reliability issues and researcher degrees of freedom, they did not necessarily undermine the production of a robust and credible account of the relationship between religion and early science.

Ultimately, a project to assess the robustness reproducibility of publications in the American Economic Review (Campbell et al., 2024) also reanalyzed some cliometric papers (e.g., Angelucci et al., 2022; Ashraf & Galor, 2013; Berger et al., 2013). At the very least, these papers were not excluded from the general observation that the analyses conducted by the original authors tended to yield higher effect sizes and were more often significant than those conducted by the replication teams.

The latter notion is reinforced by several research controversies over the past two decades, where commentaries analyzing the same research question in different ways contradicted the original findings (e.g., Albouy, 2012, cf. Acemoglu et al., 2012; Guinnane & Hoffman, 2022, cf. Voigtländer & Voth, 2022). Thus, there seems to be some analysis heterogeneity in some individual cases.

What should we conclude from this short overview? On the one hand, it demonstrates the possibility that different research designs and analyses can induce interpretation-changing differences in results and that some publication bias and selective reporting are going on in quantitative historical or cultural research. On the other hand, these notions do not much more than thwart universal statements about the non-existence of such problems in the arts and, due to their anecdotal character, do not allow for any statements about the extent of such heterogeneity or bias.

Researcher Degrees of Freedom in Cliometrics and Cultural Research

Adding to our (weak) conclusion that researcher degrees of freedom can also affect topics associated with the arts, we will introduce two degrees of freedom specific to cliometric and cross-cultural research (and not included in enumerations of researcher degrees of freedom in other disciplines, such as psychology; cf. Wicherts et al., 2016): the selection of (growth) control variables and a reference year.

(Growth) Control Variables

Apparently, cross-cultural researchers like growth and GDP regressions (e.g., Acemoglu et al., 2005; Berggren et al., 2011; Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2017). However, they can hardly ever assume that the relationship between their predictor of interest and growth or GDP is unaffected by confounders, so that a set of control variables has to be determined. Defining such a set is not easy—for instance because many controls, such as education and income, are highly correlated with one another—and the outcomes are very different: some papers control for geographical and religious factors (e.g., Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2017), while others exclude these factors and instead focus on economic variables such as inflation rates, openness to foreign trade, or government expenditures (e.g., Berggren et al., 2011), and others again add historical variables such as the year of independence or war history (Acemoglu et al., 2005).

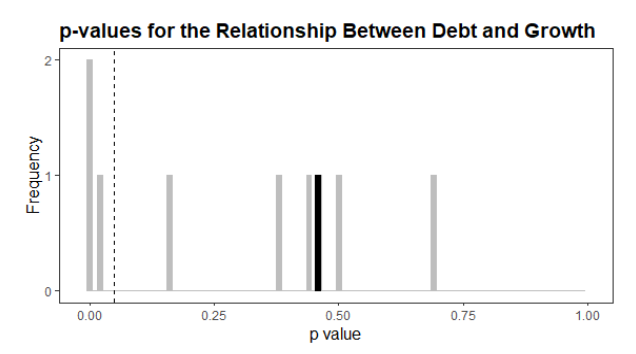

Thus, researchers can choose from a bunch of reasonable combinations of control variables. Does this affect the outcomes? To test this, we ran multiple analyses about the relationship between general government debt and growth rates across a sample of countries worldwide.³ Working with a set of nine widely used control variables,⁴ we ran one analysis with all control variables, and nine additional analyses where we removed one of the controls. The distribution of the p-values is displayed below.

First, the black bar shows the p-value for the analysis using the complete set of control variables. Here, the relationship between debt and growth rates was insignificant (p = .458). Yet, when removing one of the nine control variables, the results can change drastically, as demonstrated by the grey bars: Two analyses (one without life expectancy and the other without inflation rates) found that higher debt levels were highly significantly associated with lower growth, with p-values of .003 and < .001, respectively. Additionally, another analysis (this time without investment levels) detected a significant negative relationship, too, p = .023.⁵ All remaining analyses were, however, not even close to being significant.

Why do p-values change when we include or exclude different control variables? Generally, there are two main reasons for this:

Control variables might reduce noise in the outcome variable: By including control variables, we might explain some of the variation in the outcome (here: growth rates). This reduces the "noise" in its values, so it is easier to detect the effect of the predictor of interest (here: debt).

They might, however, also account for relationships between variables: Control variables may be related to both the predictor of interest and the outcome. By including these controls, we isolate the unique contribution of debt to growth rates. Without them, we might mistakenly attribute some of the control variable's effect to debt.

The second case is particularly interesting because it changes how we (should) interpret the regression results. For example, if we do not control for inflation rates, the observed relationship between debt and growth might not be due to debt itself reducing growth. Instead, it could reflect the fact that higher debt levels are often associated with high inflation, which in turn hampers growth. In this case, failing to control for inflation could lead us to a misleading conclusion about the causal relationship between debt and growth. However, not many papers reporting growth regressions seem to discuss how their composition of control variables affects the outcomes; instead, it appears more common to choose a particular set based on previous research (e.g., a popular paper by Barro, 1991) that might be more or less appropriate for different regressions.

This quick example demonstrates that the set of control variables heavily influences whether a predictor for economic growth will be significant or not.⁶ It also shows that, given the lack of consensus about which variables to control for, researchers have a fair chance of generating positive results by playing with the controls.

Year

Another standard research design in cliometrics or cultural research is the cross-section, where we score countries on a predictor and then examine whether this predictor is significantly related to an outcome: Does an individualistic (vs. collectivistic) culture relate to higher productivity (Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2017)? Do countries with low, medium, or high genetic diversity have a higher GDP per capita (Q. Ashraf & O. Galor, 2013)? For such comparisons, we must select a reference year—does an individualistic culture relate to higher productivity in 2000, 2010, or 2020?

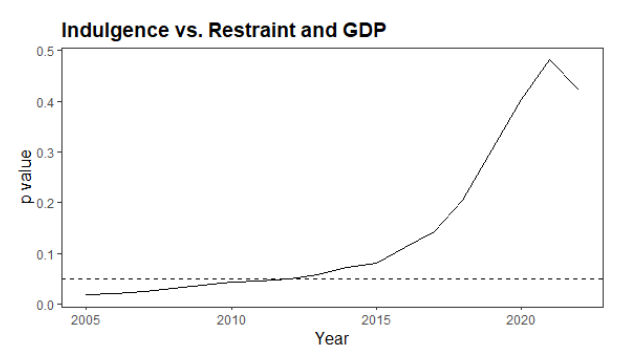

To demonstrate that the year matters, we set up a quick example analysis: Is indulgence vs. restraint (i.e., the degree to which relatively free gratification of basic human needs is restricted by, for instance, social norms; Hofstede, 1980) associated with GDP per capita?⁷ The graphic below shows the p values for the years between 2005 and 2022:

First, the analyses for all years indicate that indulgence is positively related to GDP per capita. However, while this relationship is significant for the years between 2005 and 2012 (and marginally significant until 2015), it becomes insignificant afterward. This could be due to some short-term developments: for example, some very restrained countries (e.g., China and Pakistan) experienced relatively high growth rates during our investigation period, while some very indulgent countries (e.g., Argentina and Brazil) struggled more. Still, it could also reflect that the relationship between indulgence/restraint and economic performance became weaker over time. In any case, the common practice of picking one year seems misplaced for this particular analysis, as developments characteristic of that year but not of the research question of interest could determine whether we observe a (significant) relationship or not. Instead, it might be more appropriate to look at the development of the relationship over time: accounting for variation between the results of different years might not only prevent false positives (or negatives) but also detect long-term developments in a relationship that could, in turn, be exploited for theory-building (e.g., Maseland, 2021).

The analyses reveal a consistent positive relationship between indulgence and GDP per capita across all years. However, this relationship is significant only between 2005 and 2012 (and marginally significant until 2015) but becomes insignificant in later years. This shift could reflect short-term developments during the study period: for instance, some highly restrained countries, like China and Pakistan, experienced relatively high economic growth, while the economies of more indulgent countries, such as Argentina and Brazil, struggled at the start of the millennium. Alternatively, the fluctuations might also indicate that the relationship between indulgence/restraint and economic performance has weakened over time.

In either case, relying on data from a single year seems problematic for this kind of analysis. A snapshot from one year could be heavily influenced by events specific to that period that determine the answer we receive to our broader research question. It would be more meaningful to examine how this relationship evolves over time. By considering variations across multiple years, researchers can not only reduce the risk of false positives (or negatives) but also uncover long-term trends that might inform theory development (see, e.g., Maseland, 2021). Such an approach could help identify persistent patterns or shifts in the relationship, providing valuable insights into the dynamics between cultural traits and economic performance.

Conclusion

This blog post aimed to establish two fundamental notions: First, quantitative analysis in the arts (e.g., history, cultural research) also involves researcher degrees of freedom, which can lead to meaningful variations in results. Second, these degrees of freedom can be strategically utilized to generate significant findings.

Together, these two notions could lead to an inflated number of false-positive results. Indeed, the limited evidence we have so far suggests the existence of at least some publication bias and/or selective reporting in the quantitative humanities. Finally, while research in the humanities may not share the same topics or degrees of freedom as fields like psychology or medicine, the approaches that meta-researchers have developed in recent years (e.g., multiverse analyses, p-curves) could provide a good starting position for addressing publication bias and selective reporting in the arts as well.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth. American Economic Review, 95(3), 546-579. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201305

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation: Reply. American Economic Review, 102(6), 3077-3110. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.3077

Albouy, D. Y. (2012). The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation: Comment. American Economic Review, 102(6), 3059-3076. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.3059

Angelucci, C., Meraglia, S., & Voigtländer, N. (2022). How Merchant Towns Shaped Parliaments: From the Norman Conquest of England to the Great Reform Act. American Economic Review, 112(10), 3441-3487. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20200885

Ashraf, Q., & Galor, O. (2013). The “Out of Africa” Hypothesis, Human Genetic Diversity, and Comparative Economic Development. American Economic Review, 103(1), 1-46. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.1.1

Astington, J. W. (1999). The language of intention: Three ways of doing it. In P. D. Zelazo, J. W. Astington, & D. R. Olson (Eds.), Developing theories of intention. Erlbaum.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230-244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.230

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937943

Berger, D., Easterly, W., Nunn, N., & Satyanath, S. (2013). Commercial Imperialism? Political Influence and Trade During the Cold War. American Economic Review, 103(2), 863-896. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.2.863

Berggren, N., Bergh, A., & BjØRnskov, C. (2011). The growth effects of institutional instability. Journal of Institutional Economics, 8(2), 187-224. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1744137411000488

Bratman, M. E. (1987). Intention, plans, and practical reason. MIT Press.

Campbell, D., Brodeur, A., Dreber, A., Johannesson, M., Kopecky, J., Lusher, L., & Tsoy, N. (2024). The Robustness Reproducibility of the American Economic Review (124). https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/295222/1/I4R-DP124.pdf

Cova, F., Strickland, B., Abatista, A., Allard, A., Andow, J., Attie, M., Beebe, J., Berniūnas, R., Boudesseul, J., Colombo, M., Cushman, F., Diaz, R., N’Djaye Nikolai van Dongen, N., Dranseika, V., Earp, B. D., Torres, A. G., Hannikainen, I., Hernández-Conde, J. V., Hu, W.,…Zhou, X. (2018). Estimating the Reproducibility of Experimental Philosophy. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 12(1), 9-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-018-0400-9

De Rijcke, S., & Penders, B. (2018). Resist calls for replicability in the humanities. Nature, 560(7716), 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05845-z

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Roland, G. (2017). Culture, Institutions, and the Wealth of Nations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(3), 402-416. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00599

Guinnane, T. W., & Hoffman, P. (2022). Medieval Anti-Semitism, Weimar Social Capital, and the Rise of the Nazi Party: A Reconsideration. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4286968

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage Publications.

Knobe, J. (2003). Intentional action in folk psychology: An experimental investigation. Philosophical Psychology, 16(2), 309-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080307771

Latour, B. (1991). We have never been modern. Harvard University Press.

Maseland, R. (2021). Contingent determinants. Journal of Development Economics, 151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102654

Nelson, L. D., Simmons, J., & Simonsohn, U. (2018). Psychology's Renaissance. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(Volume 69, 2018), 511-534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011836

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). PSYCHOLOGY. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Peels, R., Van Den Brink, G., Van Eyghen, H., & Pear, R. (2024). Introduction: Replicating John Hedley Brooke’s work on the history of science and religion. Zygon, 59(2). https://doi.org/10.16995/zygon.11255

Rennie, D., & Flanagin, A. (2018). Three Decades of Peer Review Congresses. JAMA, 319(4), 350-353. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.20606

Voigtländer, N., & Voth, H.-J. (2022). Response to Guinnane and Hoffman: Medieval Anti-Semitism, Weimar Social Capital, and the Rise of the Nazi Party: A Reconsideration. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4316007

Wicherts, J. M., Veldkamp, C. L., Augusteijn, H. E., Bakker, M., van Aert, R. C., & van Assen, M. A. (2016). Degrees of Freedom in Planning, Running, Analyzing, and Reporting Psychological Studies: A Checklist to Avoid p-Hacking. Front Psychol, 7, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01832

Footnotes

1. For example, the theory of unconscious priming was originally corroborated by verifying the hypothesis ‘‘People walk slower when they are shown words they associate with the elderly” (Bargh et al., 1996). Compared to that, it is very hard to establish (inter-subjective) falsification of, say, the central hypothesis of Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern (Latour, 1991) “What we call the modern world is based on an ill-defined separation between nature and society.”

2. Also, an interesting account by de Rijcke and Penders (2018 suggests that the arts are more about the search for meaning than chasing after truth and perform “evaluation and assessment according to different quality criteria — namely, those that are based on cultural relationships and not statistical realities.” In this case, the problem of overconfidence in or flaws of the theoretical state of the art(s) is irrelevant and any efforts to detect such issues redundant. Still, as Peels et al. (2024) note, the arts are not entirely off the hook when it comes to truth-seeking, as they also include research questions such as whether European colonies that were poorer at the end of the Middle Ages developed better than richer colonies because they were not subject to extractive institutions (Acemoglu et al., 2002). Therefore, this blog post at least concerns questions of this type, without explicitly including or excluding any other research question from the arts.

3. Growth rates were calculated using the data from the Maddison Project Database 2023 (Bolt & van Zanden, 2023). Data about general government debt came from the Global Debt Database of the International Monetary Fund (Mbaye et al., 2018). The sources of the control variables were the Penn World Tables 10.01 (Feenstra et al., 2015), the World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2024), ILOSTAT (International Labour Organization, 2024), and Barro and Lee (2013). We used data from 2005 to 2019.

4. The control variables were GDP capita (for convergence), population growth, investment levels relative to the GDP, government share relative to the GDP, sum of imports and exports relative to the GDP, education level, inflation level, life expectancy, and labor force growth.

5. The coefficients indicate that a 25% increase in general government debt (similar to the increase in the United States during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic) decreases yearly growth rates by 0.3% to 0.4%.

6. Interestingly, the effect size estimates are rather close to one another, ranging from 0.0% to 0.4% for all (significant and insignificant) analyses. The underlying multiverse variability is 0.014 for Cohen’s f².

7. GDP data came from the Maddison Project Database 2023 (Bolt & van Zanden, 2023), and data for power distance from the Hofstede (1980) data. We performed a linear regression for each year, controlling for a standard set of geographical and religious variables already used by previous studies on the relationship between culture and economic performance (e.g., Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2017).